Folk (Browser) Interfaces

Metadata

Highlights

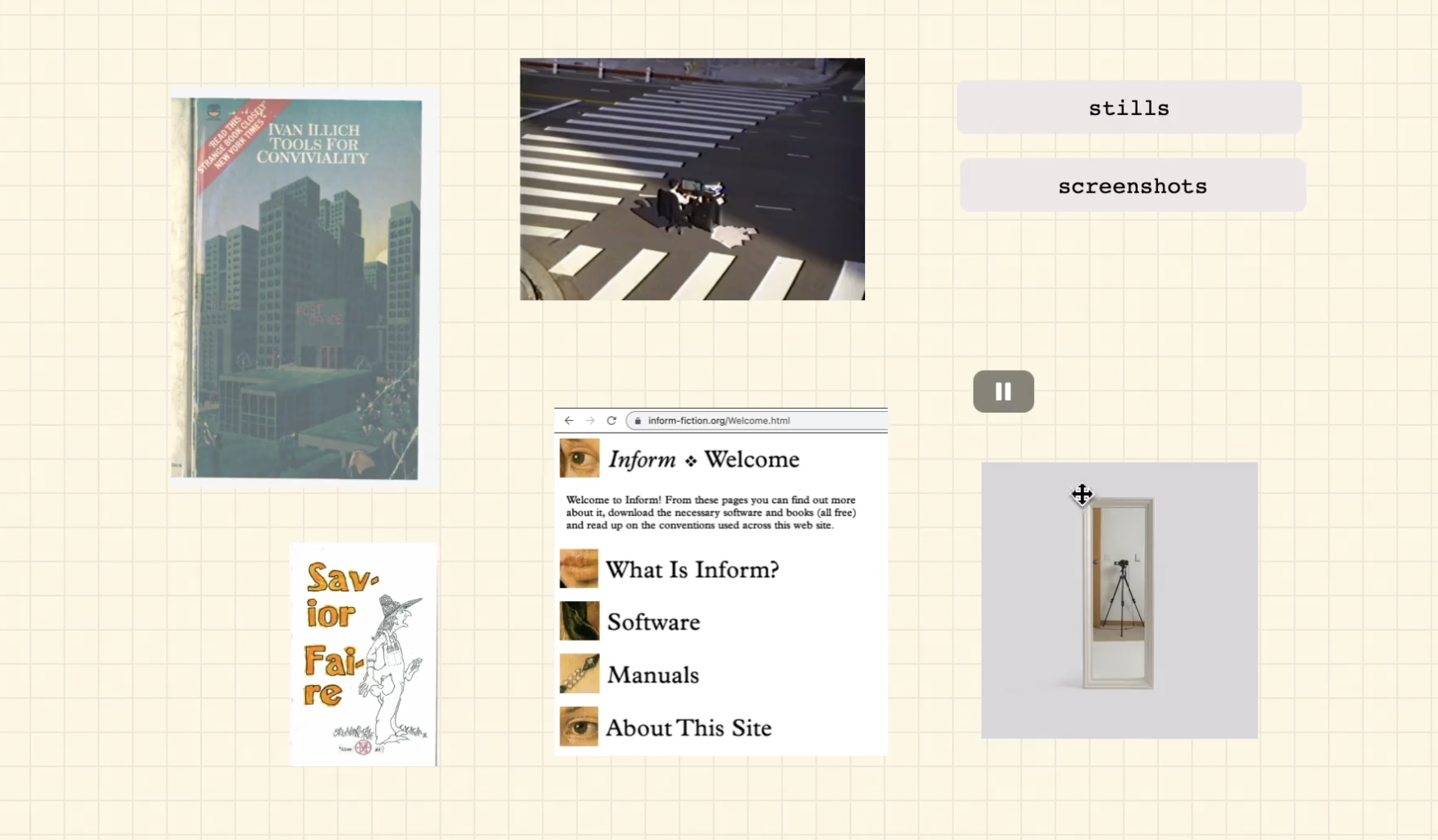

- Instead, it re-centers programming around designing powerful media interactions. This kind of interface design is intimately connected to the materiality of media and, consequently, banks on domain knowledge in, e.g., computer graphics. It’s akin to building a one-off Photoshop or Blender interface, built on robust web APIs (canvas, audio, WebGL) and libraries (Three, p5, tf.js). Exceptionally, these libraries are focused a giving you handles into media, rather than supporting an industrial mode of production. (View Highlight)

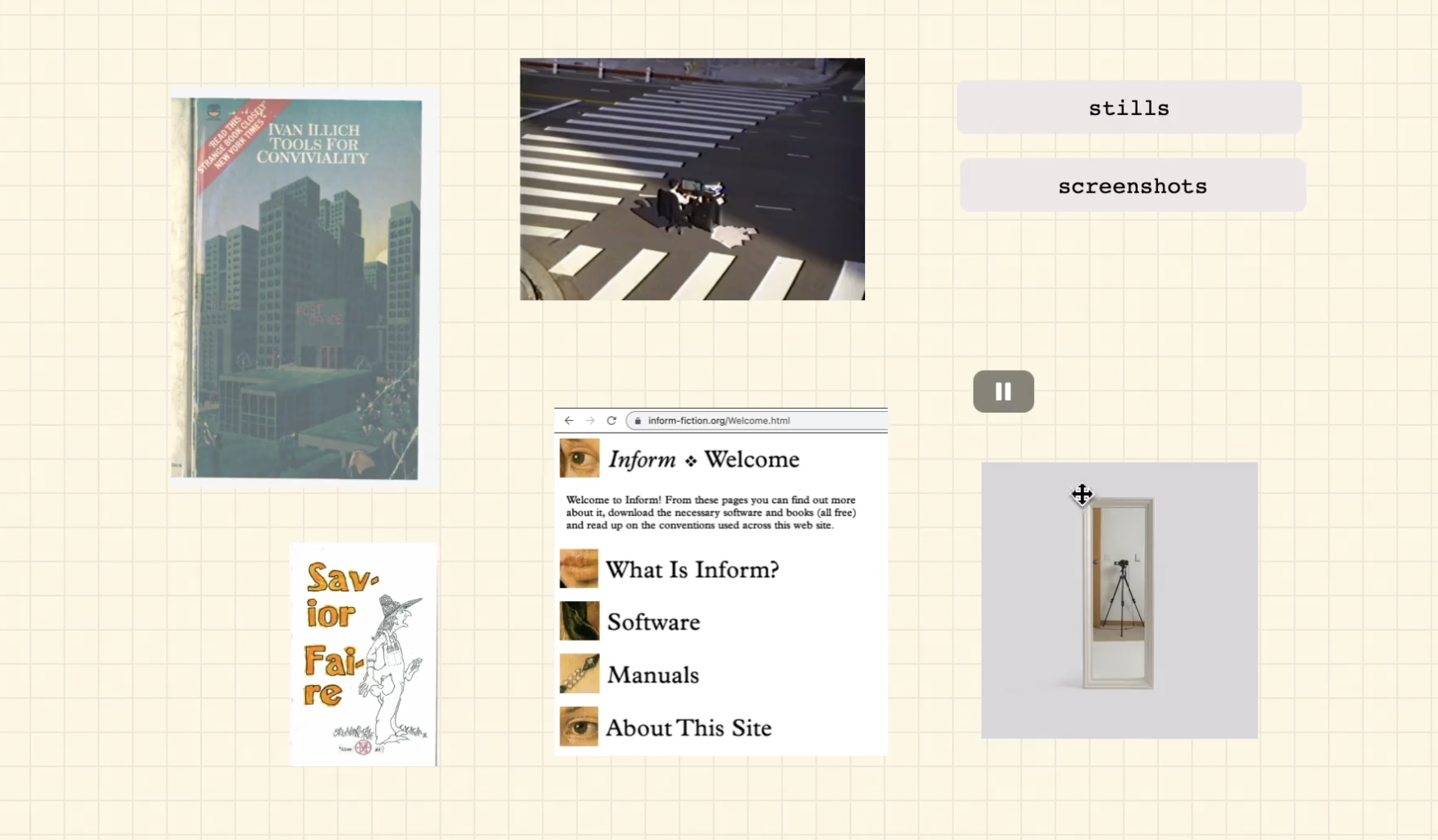

- I think of these as folk interfaces, akin to the jigs one makes in wood-working. Divorced from grandiose ambitions of building comprehensive systems, it leads the programmer to directly engage with data. I hope this mode can paint the picture of software, not as a teleological instrument careening towards automation and ease, but as a medium for intimacy with the matter of our time (images, audio, video), yielding a sense of agency with what, to most, feels like an indelible substrate. (View Highlight)

- A surplus of hand-curated media files live on our file-systems. These are artifacts we care about enough to screenshot, save as PDF, or jot down in notes. Nonetheless, it’s as if we’ve put them in deep-storage: it’s hard to do anything with them, and even rarer to mix different artifacts into a collage. One is forced to embed images and text into inextricable word documents and slides, or use an infinite canvas like Figma, at which point the files are no longer individuated, instead mere parts of a single new file. (View Highlight)

- This reconsiders the files on one’s computer, not as static assets with fixed ways of viewing, but as raw material to build with: archive bricolage. (View Highlight)

- Viewport as context: When an element is added to the canvas, it’s a fixed size relative to the viewport. To add a header, zoom out to the region that matters. To add a small comment, zoom in next to the image. The hunch is that one can establish an isomorphism between viewport and the context needed for interpreting an artifact (View Highlight)

- Instead, it’s about building a playground in which those novel computational artifacts can be tinkered with and composed, via a grammar native to their own domain, to produce the fruits of the users’ own vision. (View Highlight)

- The goal of the computational tool-maker then is not to teach the layman about recursion, abstraction, or composition, but to provide meaningful primitives (i.e. a system) with which the user can do real work. End-user programming is a red herring: We need to focus on materiality, what some disparage as mere “side effects.” The goal is to enable others to feel the agency and power that comes when the world ceases to be immutable. (View Highlight)

title: “Folk (Browser) Interfaces”

author: “cristobal.space”

url: ”https://cristobal.space/writing/folk/”

date: 2023-12-19

source: reader

tags: media/articles

Folk (Browser) Interfaces

Metadata

Highlights

- Instead, it re-centers programming around designing powerful media interactions. This kind of interface design is intimately connected to the materiality of media and, consequently, banks on domain knowledge in, e.g., computer graphics. It’s akin to building a one-off Photoshop or Blender interface, built on robust web APIs (canvas, audio, WebGL) and libraries (Three, p5, tf.js). Exceptionally, these libraries are focused a giving you handles into media, rather than supporting an industrial mode of production. (View Highlight)

- I think of these as folk interfaces, akin to the jigs one makes in wood-working. Divorced from grandiose ambitions of building comprehensive systems, it leads the programmer to directly engage with data. I hope this mode can paint the picture of software, not as a teleological instrument careening towards automation and ease, but as a medium for intimacy with the matter of our time (images, audio, video), yielding a sense of agency with what, to most, feels like an indelible substrate. (View Highlight)

- A surplus of hand-curated media files live on our file-systems. These are artifacts we care about enough to screenshot, save as PDF, or jot down in notes. Nonetheless, it’s as if we’ve put them in deep-storage: it’s hard to do anything with them, and even rarer to mix different artifacts into a collage. One is forced to embed images and text into inextricable word documents and slides, or use an infinite canvas like Figma, at which point the files are no longer individuated, instead mere parts of a single new file. (View Highlight)

- This reconsiders the files on one’s computer, not as static assets with fixed ways of viewing, but as raw material to build with: archive bricolage. (View Highlight)

- Viewport as context: When an element is added to the canvas, it’s a fixed size relative to the viewport. To add a header, zoom out to the region that matters. To add a small comment, zoom in next to the image. The hunch is that one can establish an isomorphism between viewport and the context needed for interpreting an artifact (View Highlight)

- Instead, it’s about building a playground in which those novel computational artifacts can be tinkered with and composed, via a grammar native to their own domain, to produce the fruits of the users’ own vision. (View Highlight)

- The goal of the computational tool-maker then is not to teach the layman about recursion, abstraction, or composition, but to provide meaningful primitives (i.e. a system) with which the user can do real work. End-user programming is a red herring: We need to focus on materiality, what some disparage as mere “side effects.” The goal is to enable others to feel the agency and power that comes when the world ceases to be immutable. (View Highlight)